While language learning can be a fun hobby or an extra notch to your professional belt, you can’t rely on beginner lingo to communicate your brand to your customers. Learning Hello, Goodbye, and Where’s the bus stop? in a new language is very different from navigating lost orders, finessing brand taglines, or translating product guides.

There is an art and science to language translation, encompassing complex grammatical rules and divergent writing systems to the idiomatic expressions of a native language speaker. Then, there’s the subject matter expertise — from marketing suave to healthcare, tech, and finance jargon. The tools of the translation trade can take years to master, and even the most accomplished polyglot might not have the right skills.

Let’s explore the 10 hardest languages for English speakers to learn, and the challenges they deliver:

1. Mandarin

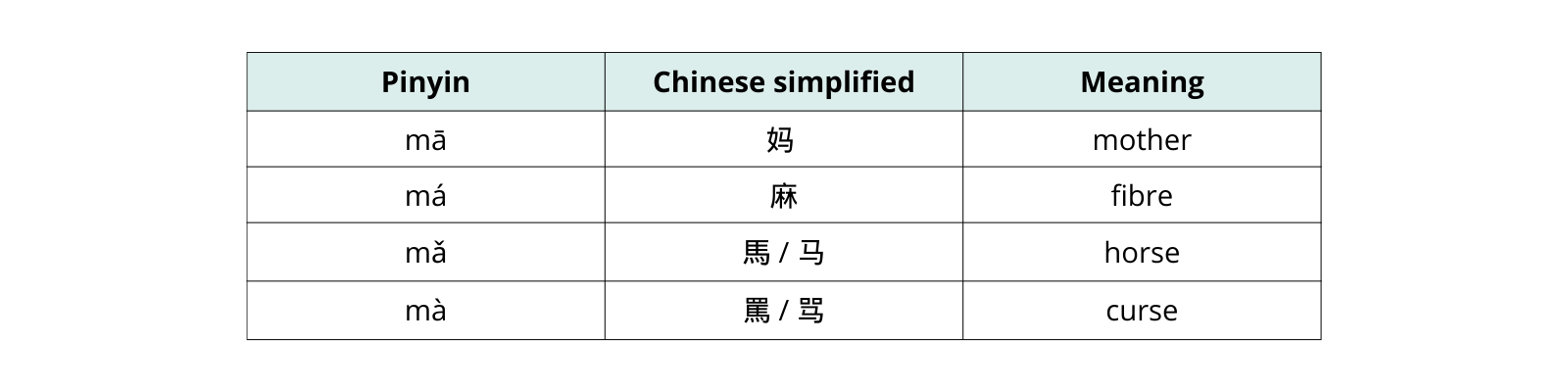

Mandarin is spoken by 70% of the Chinese population, and is the most spoken language in the world. For an English speaker, however, mastering Mandarin Chinese is a tall order: It’s a tonal language — every sound in its phonetic transcription system, pinyin, has four distinct pronunciations and meanings. The most recited example is ma — each of the words below is pronounced differently, as indicated by the accent above the ‘a’, and each pronunciation carries a different meaning:

Depending on the tone, ma can mean ‘mother,’ ‘fiber,’ ‘horse’ or ‘curse.’

Yet, Mandarin, like many Chinese languages, is also rich in homophones — words with the same pronunciation but different meanings. English speakers or learners will be familiar with such false friends as ‘abel’ and ‘able’ or ‘moan’ and ‘mown.’

Read how Mandarin homophones almost got Coca-Cola in trouble — and how they spun phonetics to their advantage.

Add to this the liberal use of idioms and aphorisms developed over centuries of poetry, politics, war, ceremony, and religion, and Mandarin becomes arguably the most difficult language for an English speaker to learn.

2. Arabic

Arabic is spoken across large swathes of Africa and the Middle East: It’s the official language in 22 sovereign states and has over 25 distinct dialects, meaning that the Arabic spoken in Egypt is different from that spoken in Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates, and can sometimes feel like a different language altogether.

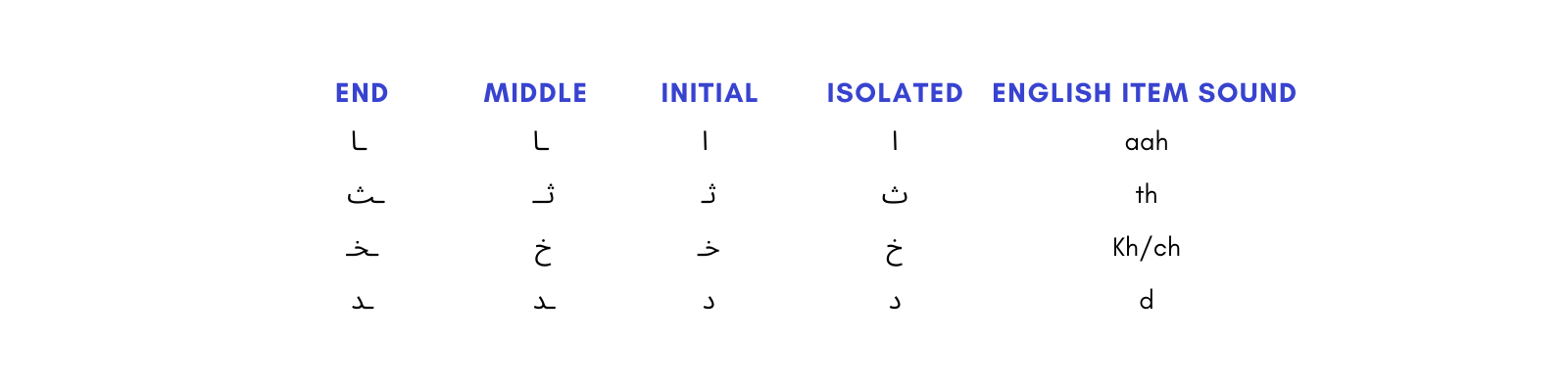

Arabic reads from right to left: However, when it comes to numbers accompanying currencies, they often tend to remain left-to-right. Most Arabic letters are written in four different forms, depending on whether they are placed at the beginning, middle, or end of a word, or as a stand-alone letter.

3. Japanese

Another Asian language in the top three, Japanese grammar can be tricky as it only has two tenses, past and non-past (which is both present and future).

Unlike most character-based writing systems, Japanese has a larger volume of characters, which must be mastered before learning to write. Japanese has three independent writing systems — hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

-

Hiragana is Japan’s version of the alphabet: With 46 characters or 51 phonetic characteristics, it’s used for native Japanese words. Most of the characters have only one pronunciation, it’s the key to understanding how Japanese words sound.

-

Katakana is used for loanwords — a word adopted from a foreign language — including technical and scientific terms, plus some plant and animal names.

-

Kanji consists of thousands of Japanese symbols that represent entire words, ideas, or phrases, and English meanings can’t always be directly translated from these.

Correctly speaking the language is the best way to break through the language barrier and build trust: So, English speakers need to master two forms of speech — polite and plain (used for casual speech).

4. Hungarian

Spoken by over 13 million worldwide, Hungarian is unlike many other European languages, including English.

Hungarian grammar rules are difficult. Rather than word order, 18+ case suffixes — the exact number is argued over — dictate tense and possession. So, to accurately convey your meaning, you need to master the grammar. However, Hungarian doesn’t have any grammatical genders — which makes it a useful language for testing gender bias in AI.

Subtle cultural elements within Hungarian make it uniquely difficult to learn: It heavily relies on idioms, which can act as a real barrier to language learning. Here’s a great example:

Annyit ér, mint halottnak a csók

Translation: It’s worth as much as a kiss is to a dead person.

Meaning: A phrase used to imply it’s pointless and won’t be appreciated.

Although an almost perfectly phonetic language, Hungarian is difficult for English speakers to speak and understand. Due, in part, to the ‘throaty’ sounds that can be tough for an English speaker’s palette and, also, the fourteen vowels, differentiated by a variety of accents, which carry different meanings.

5. Korean

Korean is the world’s most spoken language isolate — a language with no demonstrable genealogical relationship to other languages — and a very unique language. When describing an action in Korean, the word order is subject + object + action:

나는 ë¬¼ì„ ë§ˆì‹¤ — directly translates as ‘I water drink’

English speakers can also trip up over the formality levels: Very informal, informal, and formal. The language hierarchy is usually split by age, seniority, and your familiarity with the person.

Unlike other alphabets, which developed organically over time, the Korean alphabet, Hangul, was invented. While it reads left to right, like English, it also flows from top to bottom, and the characters are often taller than in Latin script, which can lead to issues when localizing mobile apps, desktop, and cloud applications. The 24 characters are all phonetic, which definitely helps with pronunciation. Yet, Korean is packed with homonyms — words that are spelled and sound the same, but have different meanings — leading to lots of false friends like ‘a bat and ball’ vs ‘the bat flew at night.’

6. Finnish

There are 6 million native speakers of Finnish worldwide, with so many regional dialects that colloquial Finnish can differ wildly from the standard. One cultural nuance does seem to remain consistent: Finns, like Danes, are more likely to cut out the small talk.

While the lettering and pronunciation are similar to English, the grammar more than makes up for any similarities: Firstly, Finnish has no future tense. Instead, speakers use the present tense and rely on context. Secondly, with 15 grammatical cases, the smallest change in word ending can significantly change its meaning, and to further disconcert learners there’s no ‘a’ or ‘the’ in Finnish.

Finnish doesn’t have any similarities to Latin or Germanic, so there’s no base connection for English speakers. That said, Finns use loanwords from other countries, like Googlata for ‘To Google’. And, several Finnish words have migrated into English vernacular — ‘sauna,’ ‘tundra,’ and ‘molotov cocktail.’

7. Basque

Like Korean, Basque is a language isolate. Primarily spoken in the Basque Country in northern Spain, it has more than a million speakers. On the whole, Basque is spoken as it is written, yet the way it’s written and spoken is distinct from any other language. This even extends to differences between the several versions of Basque: There are at least five distinct Basque dialects.

While it has borrowed vocabulary from the Romance languages, including French and Spanish, there was a strong push during the 19th Century to solidify Basque words for new phrases. Lehendakari (president) and argazki (photo) were firmly established in the dictionary by politician and writer Sabino Arana, and this collection of terms were coined sabinismos.

Unlike its Romance language neighbors, Basque doesn’t use gender cases for nouns or adjectives. A definite boon for any English-speaking learners.

8. Navajo

Navajo is spoken by 170,000 people in the Southwestern United States, primarily in the Navajo Nation, and is the most widely spoken Native American language in the United States.

Of the 33 consonants in the Navajo alphabet, there are several uncommon consonants that make pronunciation challenging for English speakers. Navajo basic word order flows subject + object + verb, and descriptions are given through verbs, so most English adjectives have no direct translation into Navajo. Indeed, ‘love’ is not conveyed by one word, it is Ayóó ánóshní which encapsulates something wider and shows that the speaker has a very high regard for the other person.

There are few loan words in the Navajo language. So instead, Western words are developed through Navajo descriptive terms. The phrase for a ‘military tank’ is chidí naa’naʼí beeʼeldÇ«Ç«htsoh bikááʼ dah naaznilígíí, ‘vehicle that crawls around, by means of which big explosions are made, and that one sits on at an elevation.’

9. Icelandic

Fewer than 400,000 people on one island speak Icelandic and the language is largely unchanged since Iceland was settled in the ninth century. Indeed, Icelandic sagas recited in the medieval period are still easily understandable to almost any modern speaker.

Rather than adopting foreign words for new concepts, Iceland coins new words — neologisms — to give contemporary meaning to old words. A great example of this is the ‘computer’ or tölva:

Tölva = tala ‘number’ + völva ‘seeress’ + sími ‘telephone’ + a revival of a disused word that meant ‘thread’

Despite being an island, with little outside influence on its own language, Icelandic has affected English, contributing the ‘th’ sound in words like ‘three’ and ‘thought’ to English. So there’s one sound language learners don’t have to learn from scratch.

On top of medieval language and neologisms, Icelandic grammar is probably the hardest aspect for English speakers to grasp. Learning Icelandic is a challenge, as to gain fluency you need to be in Iceland and make use of the local resources.

10. Polish

Polish is the second most spoken Slavic language after Russian. Yet, when it comes to translation work, Polish is considered a long-tail language — one that is less frequently localized. It has a more familiar alphabet, but a complicated gender system and free word order. This means there’s no set rule to sentence structure, as we have in English with subject + verb + object, to tell us helpful things, like who is doing what:

I fed the cat this morning

But in Polish, the word order can change to:

I fed this morning the cat

Or

This morning the cat I fed

In English, this last sentence could leave you scratching your head about who was fed to whom.

Polish also retains the old Slavic system of cases: Seven cases for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives. So, unlike English text, Polish words change depending on the context. Lastly, even though Polish words are spoken like they’re written, it’s packed with consonant clusters, so it can be hard to get your tongue around all the different sounds in Polish pronunciation.

Want to learn more about these languages? Download our language guides here.

Luckily, you don’t have to master any new languages to connect with your customers. Our hybrid approach to AI-powered machine translation combined with our network of 100,000 active editors covering 130 language pairs (and growing), delivers the speed, quality, and scale you need to translate your business.