I don’t know exactly how the trend started, but a few years ago, overnight, “underground” Chinese restaurants became all the rage. By underground, I don’t mean located at a subzero level, tucked away in the tunnels of the subway between the luggage storage and the express manicure shops. I mean illegal. The sort of restaurant, if you can call it that, that’s nothing other than a family apartment turned diner in the evenings.

You can’t pay by credit card and there is a very high chance your drinks will be brought to the table by one of the family’s children. But illegal Chinese restaurants are still great — the food is usually better and more authentic than at Chinese food chains — and make for a very fun experience.

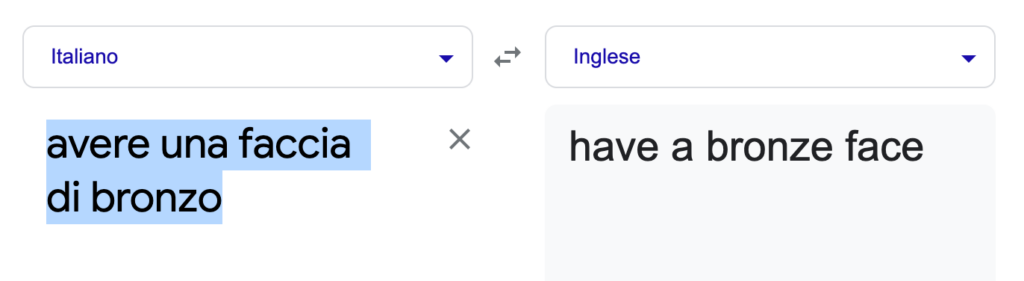

My favorite part is trying to navigate the menus. If you steer away from the simpler dishes of chicken or shrimp with a side of vegetable noodles or rice, you find yourself wondering what the roughly translated spicy garden shovels and pork à la fish can possible be.

Mistranslated food items are often amusing. As is the machine translation that turns the most innocent of sentences into a curse-filled statement. But what happens when context is more important than content?

Translation isn’t simply a matter of taking each isolated word and finding its equivalent in a different language, as I’m guessing the folks over at the illegal Chinese place did. Words in speech or in a text rarely stand alone; they have a connection to the other words around them. They are also spoken in specific social, economic, political or cultural conditions.

In a political context, mistranslations and other language barriers can take on a more significant role, as a simple mistake might possibly lead to an act of war.

The sound of silence

On July 26th 1945, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China sent an ultimatum demanding the surrender of all Japanese troops to end World War II. In this document, that became known as the Potsdam Declaration, they stated that if Japan did not surrender they would face “prompt and utter destruction”.

Pressured by newspaper reporters in Tokyo, Japan’s Prime Minister, Kantarō Suzuki, had to say something about the ultimatum, even though no formal decision had been taken. Therefore, Suzuki replied that he “refrained from comments at the moment.” This would have been the correct translation; however, international news agencies reported something else.

According to an article by State Senator John J. Marchi, published in the New York Times in 1989, there was one word that was responsible for the misunderstanding. Mokusatsu —“a word that can be interpreted in several different ways but that is derived from the Japanese term for ‘silence’” — was the term used to express Suzuki’s idea.

So, instead of saying something like “the Japanese prime minister was withholding comment”, the media reported to the world that, for the Japanese government, the ultimatum was “not worthy of comment.”

What then followed went down in History as, so far, the only use of nuclear weapons in armed conflict: on August 6th 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and, three days later, a second one fell on Nagasaki, claiming the lives of over 200,000.

A5, destroyer hit

Less than 20 years later, on August 2nd 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the destroyer USS Maddox. The American ship had been cruising around the Tonkin Gulf when three North Vietnamese patrol boats began to chase it down. By the end of the chase, the Americans sunk one of the North Vietnamese boats and managed to escape with no casualties.

A couple of days later, the National Security Agency (NSA) intercepted communications from the North Vietnamese and concluded that another attack had occurred.

However, according to NSA historian Robert J. Hanyok, that transmission was interpreted incorrectly. The phrase “we sacrificed two comrades” — presumably used by the North Vietnamese to describe casualties among their own men — was translated as “we sacrificed two ships.” This mistake misled the US into thinking that a second battle had taken place and that the North Vietnamese had lost two ships.

No one can say for sure whether the mistranslation was a deliberate falsification by the NSA or simply went uncorrected, since the original Vietnamese version of the intercept is missing from the NSA archives.

But President Lyndon B. Johnson cited the supposed attack to convince Congress to authorize broad military action in Vietnam.

No uranium to see here

More recently, in 2003, George W. Bush, then President of the United States, addressed Congress in his State of the Union speech. For most of it , he outlined the justifications to invade Iraq, confidently stating that “the British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa” to develop a nuclear bomb.

A couple of months later, the United States along with the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland, invaded Iraq.

However, as the world would soon come to realize, Iraq was in no possession of any weapons of mass destruction, had no nuclear program, and hadn’t bought any uranium from Africa, as initially thought. What George W. Bush stated in his State of the Union speech wasn’t true. So why did he think it was?

According to Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Seymour M. Hersh, it was partially because “the CIA had recently received intelligence showing that, between 1999 and 2001, Iraq had attempted to buy five hundred tons of uranium oxide from Niger, one of the world’s largest producers.”

The CIA took more than three weeks to translate and analyze the documents, which were considered highly classified and briefed only to the highest levels of American and British governments in secure facilities.

But that story quickly fell apart when Mohamed El Baradei, the director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) informed the public that the documents in question were false. One senior IAEA official went further and stated:

These documents are so bad that I cannot imagine how they came from a serious intelligence agency. It depresses me, given the low quality of the documents, that it was not stopped. At the level it reached, I would have expected more checking… They could be spotted by someone using Google.

It’s tempting to think that if the documents had been seen and translated sooner, the build-up to war might have been averted. And although this wasn’t exactly a case of a mistranslation, it was still one where a language barrier influenced how everyone involved handled the situation.

Hiroshima, Vietnam and Iraq are bonded by much more than the tragedies of war. All three events might have turned out rather differently, or have been prevented altogether, had the parties involved paid attention to not so minor details in translation.

But alas, they didn’t, and the world was never the same.

The post Translation mistakes that (might have) led to war appeared first on Unbabel.